Cory Booker Challenges America’s Disneyfied History – By Edward-Isaac Dovere (The Atlantic) / Aug 8 2019

In a new interview, the senator from New Jersey and 2020 Democratic candidate speaks candidly about race and white-supremacist violence.

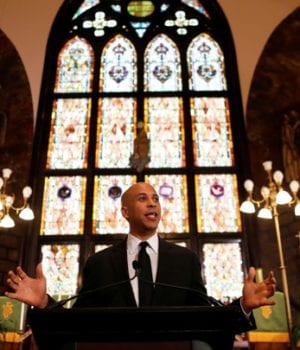

CHARLESTON, S.C.—In the basement of Mother Emanuel, Cory Booker’s eyes turned red. The senator from New Jersey and 2020 Democratic candidate had just addressed a small crowd that had gathered in the church sanctuary upstairs. “The act of anti-Latino, anti-immigrant hatred we witnessed this weekend did not start with the hand that pulled the trigger,” Booker told the room. “To love our country in this moment means that we have to step outside our comfort zones and confront ourselves.”

But the families of the murdered that Booker has faced over and over again, first as mayor of Newark, New Jersey, and later as a U.S. senator, are never interested in high-mindedness, he told me. Nobody who’s grieving wants to hear a beautiful turn of phrase. There’s nothing an exasperated TV appearance can do for their pain.

“Your words don’t matter,” Booker told me, sitting in the pastor’s office at Mother Emanuel, one room over from where, four summers ago, a white supremacist killed nine people, including then-Pastor Clementa Pinckney. “It’s your heart, your spirit, in moments like that,” Booker said, thinking back on the funerals and vigils he’s participated in. “There are no words that work. There’s no word that can replace the loss of a loved one. People want this to stop, this nightmare to stop.”

Aides told me that Booker worked through the night on the speech he delivered yesterday morning in an attempt to sound more didactic than in his usual emotional calls to action—“A reckoning with our past and present, and hope for a way out” is how a top aide summed up the thinking on the speech to me. He wasn’t going for tears. (These aides spoke anonymously to discuss the internal mechanics of the campaign.)

Booker preaches out on the trail, but at that church yesterday, for this speech between what was supposed to be a standard South Carolina campaign stop and a trip to the Iowa State Fair, he wanted to be more direct. It’s true, Booker said, Americans are just as conditioned to reactions to mass shootings—with Democrats speaking out, Republicans ducking comment for a few weeks, and pundits writing indignant columns—as they are to the shootings themselves. “You fail when you give up. And I refuse to fail,” Booker told me. (My full conversation with Booker is available on the Radio Atlantic podcast.)

Four years ago, inside the TD Arena at the College of Charleston, Barack Obama started singing “Amazing Grace” at a memorial service for those murdered at Mother Emanuel. Yesterday morning, Booker was at the church trying to believe there’s any grace left. Is Donald Trump, whose political sense of himself is still so much a reaction to Obama, a racist? Did Trump’s tweets about immigrants “invading” inspire the El Paso shooter? Booker made clear that he stands with most of the 2020 Democratic candidates in thinking that the answer to both is yes, but he warned the audience against letting “these conversations devolve into the impotent simplicity of who is or isn’t a racist. Because if the answer to the question ‘Do racism and white supremacy exist?’ is yes, then the real question isn’t ‘Who is or isn’t a racist?’ but ‘Who is and isn’t doing something about it?’”

The only way to end the nightmare, Booker told the room, is to shatter the fantasy of an America without horrors.

There’s a former slave market one mile from Mother Emanuel. Fort Sumter, where the first shots of the Civil War were fired, is just across the water from all the beautiful wisteria-covered homes of Charleston. Mother Emanuel itself was burned down by an angry white mob in 1822, and the congregation met in hiding for years.

“The idea that we’re going to create some Disney-movie version of our history is offensive to me—it diminishes who we are by not telling the truth of who we are,” Booker told me. “Knowing the bloody, violent truth of our past empowers me and encourages my hope for what we have the capacity to do in our present. But it’s not easy. It’s not. What is easy is what Donald Trump does for short-term, pitiful political gain: to demonize ‘the other,’ other Americans, demean and degrade them. Politicians like this—this is a major part of our American story. I have no choice but to stay in this fight. Even if you lose day after day, [even if you] have to go to funeral after funeral after funeral, even if you lock—as I did—lock myself in the mayor’s office from time to time and just cry, you’ve got to get up off your knees and go back into the fight. That’s what this moment calls for. And none of us can show greater courage than those people in our past who saw more wretchedness, more violence, more hurt, and more pain, but kept on going, and bequeathed to us a nation that was better than when they found it.”

In his speech at the church, Booker quoted Galatians (“God is not mocked; for whatever a man sows, this he will also reap”), James Baldwin (“To be passive is to be complicit”), Martin Luther King Jr. (“It may be true that the law cannot change the heart, but it can restrain the heartless”), and Toni Morrison, whose death was announced the day before Booker’s address (“The function of freedom is to free somebody else”). He called for Americans to be the new generation of freedom fighters. But, Booker told the crowd, that comes only from going beyond calling for background checks or trying to parse each shooter’s motives. He invoked the gun violence he’s seen in Newark, but also the way that America has responded to the rampant use of opioids in rural areas in such a different way than how it reacted to the crack epidemic in the inner cities in the 1980s. I mentioned to Booker that 48 people were shot over the weekend in Chicago while the attacks were going on in Texas and Ohio. He told me the common thread is that America’s leaders, and Americans overall, act like “certain lives don’t matter … and I think that’s insidious.”

The fundamental question of Booker’s 2020 candidacy, as he and his staff know well, is whether Americans—and to start with, Democratic primary voters—actually want to be brought together. So much of the Democratic primary campaign so far has been defined by a Twitter-centric progressive base out for blood, demanding vengeance for a long list of violations and declaring any candidate unwilling to raise a pitchfork a lost cause. But moments of national tragedy are exactly when people tend to want to believe in something more. On Monday, Trump’s perfunctory call for unity followed a rally last Thursday where he said Democrats were destroying America.

Booker’s rivals have had various reactions to the recent tragedies. Former Representative Beto O’Rourke of Texas peppered in curse words as he scolded reporters failing to see the racism of the president, living out the exasperation and pain in real time.

Former Vice President Joe Biden is using the El Paso shooting to renew his challenge to Trumpism as a “battle for the soul of America.” Senator Michael Bennet of Colorado tweeted, “If you elect me president, I promise you won’t have to think about me for 2 weeks at a time.” Other candidates have talked up the steps they’d take on gun control if elected, and have called for action, the standard whenever there’s a shooting. (Booker’s gun plan, released in May, was widely praised at the time by advocates as the most detailed of the field.)

At the church, Booker spoke, as he always does, about love, including radical love. After the speech, he talked with me about “seeds of hope,” calling himself “a prisoner of hope” living “in a distraught present.”

Top Democrats watching the race closely have viewed his 2020 campaign as “waiting to break” for so long that some are starting to doubt the break will ever actually come—even with a widely acknowledged success on the debate stage in Detroit last week. For a candidate whose messaging is focused on fighting hate, combatting gun violence, and calling for unity, I asked Booker, does it finally feel like the purpose of his campaign is coming together?

“It’s reaffirmed what I said at the very beginning of this campaign: I am running because of the forces trying to rip our country apart. I’m running because I believe we need a president that can heal and bring people together,” Booker told me. “I’ve always known that the antidote to Trump’s demeaning and degrading and divisiveness is the next leader needs to be one that has the driving purpose to be unifying, healing, and speaking openly about civic grace and decency and love.”

There’s a reason, Booker told me, why Jimmy Carter won after Watergate, why Bill Clinton won as he “spoke openly about the best of American virtues,” why Obama beat Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary in 2008. “I can’t honestly sit here and tell you I remember the differences between Senator Clinton and Senator Obama’s health-care policy,” Booker told me. “But I can tell you that Obama spoke to my heart, and he spoke to my gut, and he spoke to my spirit.”

Even before the 2015 Charleston rampage—for many, the first time they heard the phrase white supremacy rebranded as domestic terrorism—Mother Emanuel was thick with history. Anyone who knew Charleston knew the church’s tall spire long before the shooter walked in that day, June 17, 2015—by chance, one day after Trump descended the escalator inside Trump Tower and called Mexicans rapists as he launched his campaign for president. But since the shooting, Mother Emanuel has had the air of a place apart. Even now, there are no metal detectors at the entrance. I had the experience of sitting in the back last fall, watching another politician (and at that point, an expected presidential candidate), former Massachusetts Governor Deval Patrick, respond to the Tree of Life synagogue shooting in Pittsburgh. I was welcomed and encouraged to join the prayers by an enthusiastic man who’d never seen me before and didn’t realize I was there as a reporter.

Yesterday was Booker’s third time at Mother Emanuel. I asked him what walking into this space felt like, knowing the horror that had happened here, and the way the community responded with forgiveness and the state responded with, not least, removing the Confederate flag from the capitol grounds.

“It is the challenge of both holding physical pain and grief in your heart at the same time that you hold hope and inspiration,” he told me. “I think in many ways what I’ve learned is a story of black America, is this awful wretchedness and pain, unimaginable suffering, combined with the powerful testimony of perseverance of faithfulness and ultimately the exaltation of advancement.”

After we spoke, Booker left for the airport, back into the rush of the trail, to keep scraping along in hopes of coming closer to real contention in the race. (He’s currently at about 2 percent in most polls.) Those who had gathered to watch his speech were already gone, as were the reporters who’d flown in to see what Booker would say. Noon struck. The Mother Emanuel bells started ringing. The tune was a familiar one: “Amazing Grace.”

https://www.theatlantic.com/politics/archive/2019/08/cory-booker-white-supremacy/595684/